In Egypt, campaigns are calling for little girls no longer to be circumcised. But while the state wants to protect future generations, the 28 million women who have already been mutilated have only one private clinic to help them.

Nourhane, in her thirties, took the plunge at the end of 2021. This resident of Alexandria, in the coastal north, who speaks under a pseudonym, turned to surgeon Reham Awwad to “become once again the one who decides for (her) body”.

Eight months after a reconstruction operation, her chronic pain has been replaced by “completely new sensations” and “a clear physical and psychological improvement,” she explained.

It has only been possible to carry out this type of operation in Egypt since 2020.

By founding Restore FGM, Dr Awwad and her colleague Amr Seifeldin have offered victims a rare space in a country where disclosing excision is still taboo.

Surrounded by psychologists, they offer therapies, plasma injections to regenerate damaged tissue and clitoral reconstruction.

“Surgery is the last resort”, insists Dr Awwad, adding that plasma injections combined with psychological support “can reduce the need for surgery by 50%” and avoid another traumatic procedure.

This is the option being considered by Intisar, who is also speaking under a pseudonym. “Something in me has been broken, and I want to repair it”, told the forty-year-old.

When she was 10, “my grandmother took me to a doctor who excised me”, and she kept saying “it’s for your own good, you’re better off like that”. Despite being a doctor and the headmistress of her school, her parents had agreed to the operation during the summer the peak of girl circumcisions, according to campaigner Lobna Darwish.

An old tradition now medicalized

To combat this practice, “we need to run prevention campaigns in schools before the summer holidays”, argues Ms. Darwish, who oversees gender issues at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR).

The figures are staggering according to the authorities, 86% of married Egyptian women aged between 15 and 49 had been circumcised by 2021. UNICEF estimates that 200 million women in the world have been circumcised. More than one in ten is Egyptian.

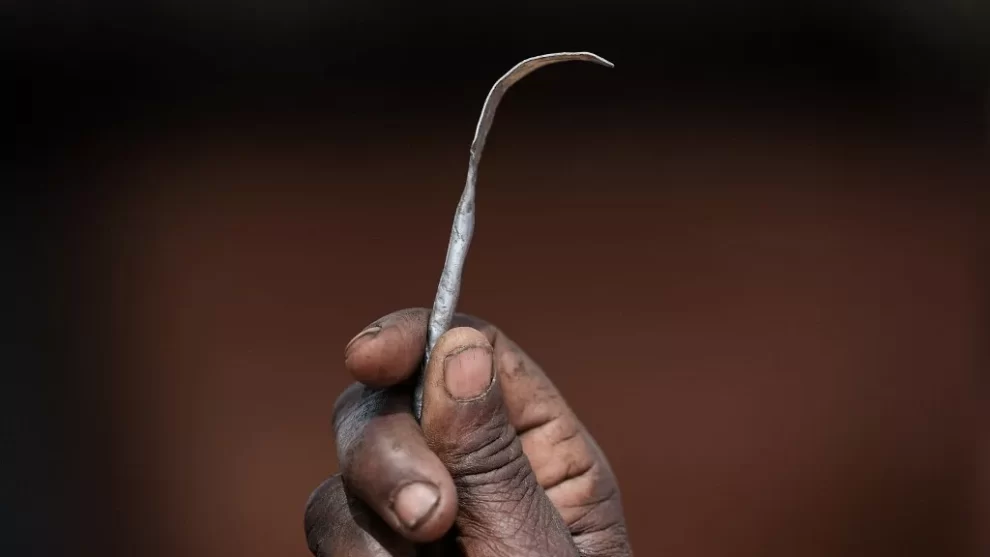

In the most populous of Arab countries, excision involves the removal of the clitoris and labia minora. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it causes pain, hemorrhage, infections, painful sexual relations and complications during childbirth.

Although illegal since 2008 and regularly denounced by the Muslim and Christian authorities, this age-old practice remains widespread in the patriarchal and conservative country, where many clinics offer it.

After years of campaigning against traditional excisers, three quarters of Egyptian women have been circumcised by a doctor, according to official figures.

“Excision cuts across all social classes,” says Intissar, now a journalist.

Promoted as a “cosmetic” operation, she continues, it is in fact aimed at “disconnecting women from their bodies and their pleasure”.

“We were told that it was religious, that it was better, cleaner”, agrees Nourhane, who was mutilated at the age of 11 with her eight-year-old sister under the gaze of the women in her family.

Egypt isn’t the only country that practices this ritual in Africa.

A mirror for self-discovery

The law regularly imposes stiffer penalties on doctors who perform excisions or on their parents.

But for Ms Darwish, this “criminalization” is counter-productive because no one wants to denounce their own family.

“What is needed above all are sex education courses” and “publicizing the toll-free number” set up by the government in 2017, she says.

For Dr Awwad, doctors also lack information: “They don’t hear about reconstructive surgery either during their studies or during their internship”, she accuses.

Women, for their part, know little about their anatomy. At every first consultation, Dr Awwad gives her patients a mirror so that they can discover their genitals.

Intissar has been there. “I found out that both my labia and part of my clitoris had been removed. I thought I’d just had a little bit of skin removed. I was very angry,” she says.

Nourhane has also experienced anger. Firstly at her mutilation, but also at the lack of help for reconstructive surgery. It took her almost a year to get a donation to cover the operation: 1,200 euros, ten times the average salary in Egypt.

“Medicines are expensive too, so the people in charge need to sort this out,” she says, and “offer reconstructive surgery in public hospitals”.

But Nourhane has already scored a victory: together with her mother, she managed to prevent the excision of her two nieces.

Source : AFRICANEWS

Add Comment