Six years ago, a Muslim boy returned red-faced from a well-known school in the northern Indian city of Agra.

“My classmates called me a Pakistani terrorist,” the nine-year-old told his mother.

Reema Ahmad, an author and counsellor, remembers the day vividly.

“Here was a feisty, little boy with his fists clenched so tightly that there were nail marks in his palm. He was so angry.”

As her son told the story, his classmates were having a mock fight when the teacher had stepped out.

“That’s when one group of boys pointed at him and said, ‘This is a Pakistani terrorist. Kill him!'”

He revealed some classmates had also called him nali ka kida (insect of the gutter). Ms Ahmad complained, and was told they “were imagining things… such things didn’t happen”.

Ms Ahmad eventually pulled her son out of school. Today, the 16-year-old is home-schooled.

“I sensed the community’s tremors through my son’s experiences, a feeling I never recall having in my own youth growing up here,” she says.

“Our class privilege may have protected us from feeling Muslim all the time. Now, it seems class and privilege make you a more visible target.”

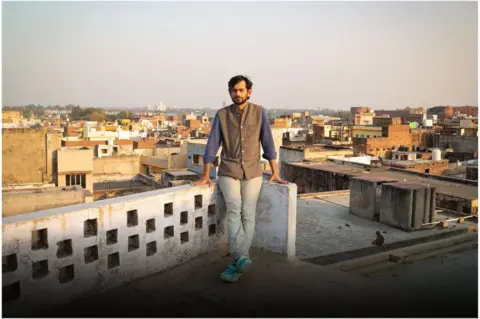

Bimal Thankachan

Bimal ThankachanEver since Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) swept to power in 2014, India’s 200 million-odd Muslims have had a turbulent journey.

Hindu vigilante mobs have lynched suspected cow traders and targeted small Muslim-owned businesses. Petitions have been filed against mosques. Internet trolls have orchestrated online “auctions” of Muslim women. Right-wing groups and sections of mainstream media have fuelled Islamophobia with accusations of “jihad” – “love jihad”, for example, falsely accuses Muslim men of converting Hindu women by marriage.

And anti-Muslim hate speech has surged – three quarters of incidents were reported from states ruled by the BJP.

“Muslims have become second-class citizens, an invisible minority in their own country,” says Ziya Us Salam, author of a new book, Being Muslim in Hindu India.

But the BJP – and Mr Modi – deny that minorities are being mistreated in India.

“These are usual tropes of some people who don’t bother to meet people outside their bubbles. Even India’s minorities don’t buy this narrative anymore,” the prime minister told Newsweek magazine.

Yet Ms Ahmad – whose family has lived in Agra for decades, counting many Hindu friends amid the city’s serpentine lanes and crowded homes – feels a change.

In 2019, Ms Ahmad left a school WhatsApp group where she was one of only two Muslims. This followed the posting of a message after India launched air strikes against militants in Muslim-majority Pakistan.

“If they hit us with missiles, we will enter their homes and kill them,” the message on the group said, echoing something Mr Modi had said about killing terrorists and enemies of India inside their homes.

“I lost my cool. I told my friends what’s wrong with you? Do you condone killing of civilians and children?” Ms Ahmad recalled. She believed in advocating for peace.

The reaction was swift.

“Someone asked, are you pro-Pakistani just because you are Muslim? They accused me of being anti-national,” she said.

“Suddenly appealing for non-violence was equated with being anti-national. I told them I don’t have to be violent to support my country. I quit the group.”

The changing atmosphere is felt in other ways too. For a long time, Ms Ahmad’s spacious home has been a hangout for her son’s classmates, regardless of gender or religion. But now the bogey of “love jihad” means she asks Hindu girls to leave by a certain hour and not linger in his room.

“My father and I sat my son down and told him that the atmosphere was not good – you have to limit your friendships, be careful, not stay out too late. You never know. Things can turn into ‘love jihad’ at any time.”

Environmental activist Erum, a fifth-generation resident of Agra, has also noticed a shift in conversations among the city’s children as she worked in local schools.

“Don’t talk to me, my mother has told me not to,” she heard one child tell a Muslim classmate.

“I am thinking, really?! This reflects the deeply ingrained phobia [of Muslims]. This will grow into something which will not heal easily,” Ms Erum said.

But for herself, she had lots of Hindu friends, and did not feel insecure as a Muslim woman.

It’s just not about the children. In his small office along a bustling Agra street, Siraj Qureshi, a local journalist and interfaith organiser, laments the fraying of the old bonhomie between Hindus and Muslims.

He recounts a recent incident where a man delivering mutton in the city was stopped by Hindu right-wing group members, handed over to the police and thrown into jail. “He had the proper licence, but the police still arrested him. He was later released,” Mr Qureshi says.

Many in the community note a shift in behaviour among Muslims traveling by train, prompted by incidents in which Muslim passengers were reportedly attacked for allegedly carrying beef. “Now, we’re all cautious, avoiding non-vegetarian food in public transport or opting out [of public transport] altogether if we can afford to,” says Ms Ahmad.

Source: BBC

Add Comment